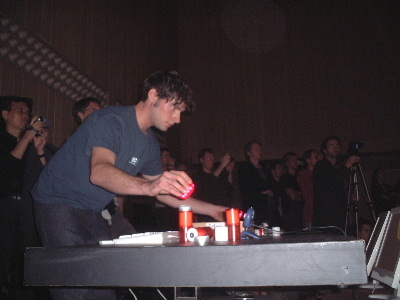

Maywa Denki Presentation at ORF

Video: Maywa Denki Performance (4 MB)

Report From Ars Electronica 2003

Published on Rhizome.org – 9/23/03

Linz, Austria

September 6 – 11, 2003

Along the banks of the Danube river in Linz, Austria, the world famous Ars Electronica festival opened with a heavy duty roster of theorists, performers, artists, and practitioners. This year’s theme, “Code: The Language of Our Time,” was meant as a starting point to examine code and software art’s development, aesthetics, and implications. Debates centered around the question: If code is the language of technology what does this mean for the future of art practice? Despite a wide range of answers from participants, the human side of the equation was ignored. For instance, how do we react to code? It might sound sentimental, but how does code make us feel? Machine code might be integral for computers to function, but ultimately humans dictate their use. I tried to answer these questions during the six day event, but felt overall that user experience remained an afterthought to most of the discussions and exhibited work.

Justin Manor on the VJ tip for Steve Reich

The symposium began with hard-hitting theorists of code and information visualization. The approach was to emphasize the framework of the conference topic as existing within a larger body of work from sociology to political to personal contexts. I arrived on the second day of the symposium, when an adamant Richard Kriesche spoke about code as a set of interconnected signs wherein code itself could be seen as art form in itself. Roman Verostko, an artist and theorist provided a nice alternative when he presented his graphic drawing machines built in the 80s as examples of rule-based sculptures illustrating how changing a single variable in a process can create infinite and unpredictable behaviors. Following this presentation, Casey Reas, co-creator of Processing (proce55ing.net), argued that programming languages are materials, like other enabling media, and that despite their flexibility, they can also be limiting. His inspiration for Processing stems from the processes of code executing, rather than the act of writing code, or the code’s output. At the Q&A session after his talk, Andreas Broeckmann (co-curator of Transmediale) posited to Reas the simple question:”Why do you program?” Of which Reas replied, “Because I have to”. Coding might be a biologic need for some, but the debate raged on as to how code can translate from one medium to the next.

Other symposium sessions focused on the scalability of code into new forms including community and networks to physical devices and objects. During the “Social Code” panel, Howard Rheingold, author of “Smart Mobs”, spoke about the battle over code where conflict of ownership ultimately curbs innovation. Florian Cramer disputed the festival’s theme by emphasizing the appropriation of code as art and how this distinction creates and artificial relationship between code and language. Looking at biometrics, Fiona Raby, formerly of the Royal College of Art, threw some humor into the mix by outlining the “BioLand” project, a virtual mini-mall of bio-metric devices and gadgets including a human DNA encoded pet pig. Also, Hiroshi Ishii, professor of Tangible Media at the MIT Media Lab, spoke about decoding code through physical interaction with objects and how by creating these dynamic relationships could contribute to a new human language of collaborative design. Finally Crista Sommerer, artist and professor at IAMAS in Japan, spoke about her various installations that attempt to transcend the aesthetics of the machine such as two haptic squash-encased devices that share people’s heartbeats across a Bluetooth connection.

Escaping the talks for some fresh air, I wandered down to the exhibition across town. Toned down from last year, the show featured a wide range of interactive projects from the CyberArts Honorary Mention category. Walking up the O.K. Center’s long concrete stairwell, visitors were tracked and illuminated by Marie Sester’s “Access”, a responsive spotlight that follows your movements as dictated by online participants. On the first floor, the Japanese-based musical group/corporation, Maywa Denki’s amazing electronic and human controlled musical instruments were set up, including several interactive guitars and drum machines with electronically controlled mallets connected to custom software running on a PC. Other highlights included the “Biker’s Horn” a saxophone like instrument with flashing lights and multiple tubes and the “Drum Shoes”, wherein the CEO of Maywa Denki wore actuated shoes with mallets as toes that were triggered by tapping his fingers on custom built gloves with keys. Down the hall was Daniel Reichmuth and Sybill Hauert’s “Instant City”, a block interface based musical system where visitors could build structures that depending on the amount of blocks placed triggered different samples. Another simple yet effective musical interface was “Block Jam”, a collection of small reconfigurable blocks with embedded LED displays that allowed people to create custom rhythms based on the blocks position, orientation, and proximity to each other. Finally, in fine contrast to the high tech installations was Iori Nakai’s, “Streetscape”, a pen-based interface that played city sounds as users traced an embossed map of Linz.

Scattered throughout the main venues were various performances and special events that kept Ars visitors occupied. The main event was Golan Levin and Zachary Leiberman’s “Messa di Voce”, an experiment in interactive 3D graphics and sound, where vocalists Japp Blonk and Joan La Barbara’s cacophonous utterances came to life amid a giant triple projection screen backdrop. Instead of focusing on a distinct theme, the piece felt more like a collection of unique vignettes that emphasized universal appeal over any distinct viewpoints. On the music side, Steve Reich’s monotonous “Drumming” performance featured countless percussionists pounding repetitive rhythms in a room of swirling visuals provided by FutureLab resident artist, Justin Manor. The last night of Ars featured the bizarre “POL – Machatronic” performance in the PostHof with actors donning robot exoskeletons while reenacting a sausage themed love story. Afterwards, the late night Code Arena at the Stadtwerkstatt pitted programmers against drunken audiences who voted for the first ever Chocolate Nica Award presented by Sodaplay creator, Ed Burton.

As the festival ended and all the code was compiled, there still seemed to be something missing. Despite all the featured examples and practice of software aesthetics in execution, code as language, input and output, and modes of representation, there was little discussion about experiencing the code itself. For instance, who uses all of the code produced? What are we thinking, feeling, and experiencing when code is used and what reactions exist in these instances? Although insight was gained on how producers and theorists of this medium postulate connections with code to cultural and social phenomenon, there was little focus on the human response. Ultimately it is this distinction which makes our experience unique and allows us to understand the technology we interact with everyday. Perhaps in an art context this might seem elusive, but the debate seemed incomplete without uncovering the fundamental source of our frustration and happiness with code.

![]()